Reproducibility Standards

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

What makes research reproducible?

How does a research compendium support reproducibility?

What are common obstacles to making research reproducible?

Objectives

Explain the requirements for meeting the reproducibility standard.

Describe the contents of a research compendium.

Recall some of the challenges that can hinder efforts to make research reproducible.

In the previous episode, we established our working definition of “reproducibility” as being able to reproduce published results given the same data, code, and other research artifacts originally used to execute the computational workflow. In this episode, we go beyond the definition of reproducibility to explore the standards by which we evaluate reproducibility.

Reproducibility Standards

In 1995, the Harvard University professor of political science, Gary King, proposed a new “replication standard,” which he considered imperative to the discipline’s ability to understand, verify, and expand its scholarship (here, King uses the term “replication,” but his use is analogous to our working definition of reproducibility):

The replication standard holds that sufficient information exists with which to understand, evaluate, and build upon a prior work if a third party could replicate the results without any additional information from the author (p. 444).

Accessibility and usability of the materials necessary to reproduce reported research results without having to resort to intervention from the original author is central to King’s standard, and, as you will learn, are at the core of curation for reproducibility practices.

Read King’s seminal article here:

King, G. (1995). Replication, replication. PS: Political Science & Politics, 28(3), 444–452. https://doi.org/10.2307/420301

Spotlight: FAIR Principles

Mention of the FAIR Principles has become ubiquitous in discussions of research data management. Some funding agencies have even cited the FAIR Principles in documents that provide guidance for their data management policies. FAIR, which stands for findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable, was developed as a set of guiding principles that help to sustain and enhance the value of data for scientific discovery, knowledge-making, and innovation, while avoiding the technical obstacles that can challenge those goals.

In the summary of the FAIR Principles below, pay particular attention to the Reusable principle, which when thinking about reproduction as one type of reuse, aligns directly with some of the standards we uphold when curating for reproducibility.

Findable

The data are uniquely identified and described using machine-readable metadata to enable both systems and humans to find the data in a searchable system.

F1. (Meta)data are assigned a globally unique and persistent identifier

F2. Data are described with rich metadata (defined by R1 below)

F3. Metadata clearly and explicitly include the identifier of the data they describe

F4. (Meta)data are registered or indexed in a searchable resourceAccessible

Access to the data (or descriptive metadata should the data no longer be available or require certain procedures for access) using the unique identifier assigned to the data is possible without the need for specialized tools or services.

A1. (Meta)data are retrievable by their identifier using a standardized communications protocol

A1.1 The protocol is open, free, and universally implementable

A1.2 The protocol allows for an authentication and authorisation procedure, where necessary

A2. Metadata are accessible, even when the data are no longer availableInteroperable

The data and descriptive metadata are standardized to enable exchange and interpretation of data by different people and systems.

I1. (Meta)data use a formal, accessible, shared, and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation.

I2. (Meta)data use vocabularies that follow FAIR principles

I3. (Meta)data include qualified references to other (meta)dataReusable

The data are presented with enough detail that it is clear to designated users the origins of the data, how to interpret and use the data appropriately, and by whom and for what purposes the data may be used.

R1. (Meta)data are richly described with a plurality of accurate and relevant attributes

R1.1. (Meta)data are released with a clear and accessible data usage license

R1.2. (Meta)data are associated with detailed provenance

R1.3. (Meta)data meet domain-relevant community standardsRead more about the FAIR Principles here:

GO FAIR. (n.d.). FAIR Principles. GO FAIR. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/Wilkinson, M. D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, Ij. J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., Blomberg, N., Boiten, J.-W., da Silva Santos, L. B., Bourne, P. E., Bouwman, J., Brookes, A. J., Clark, T., Crosas, M., Dillo, I., Dumon, O., Edmunds, S., Evelo, C. T., Finkers, R., … Mons, B. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

The Research Compendium

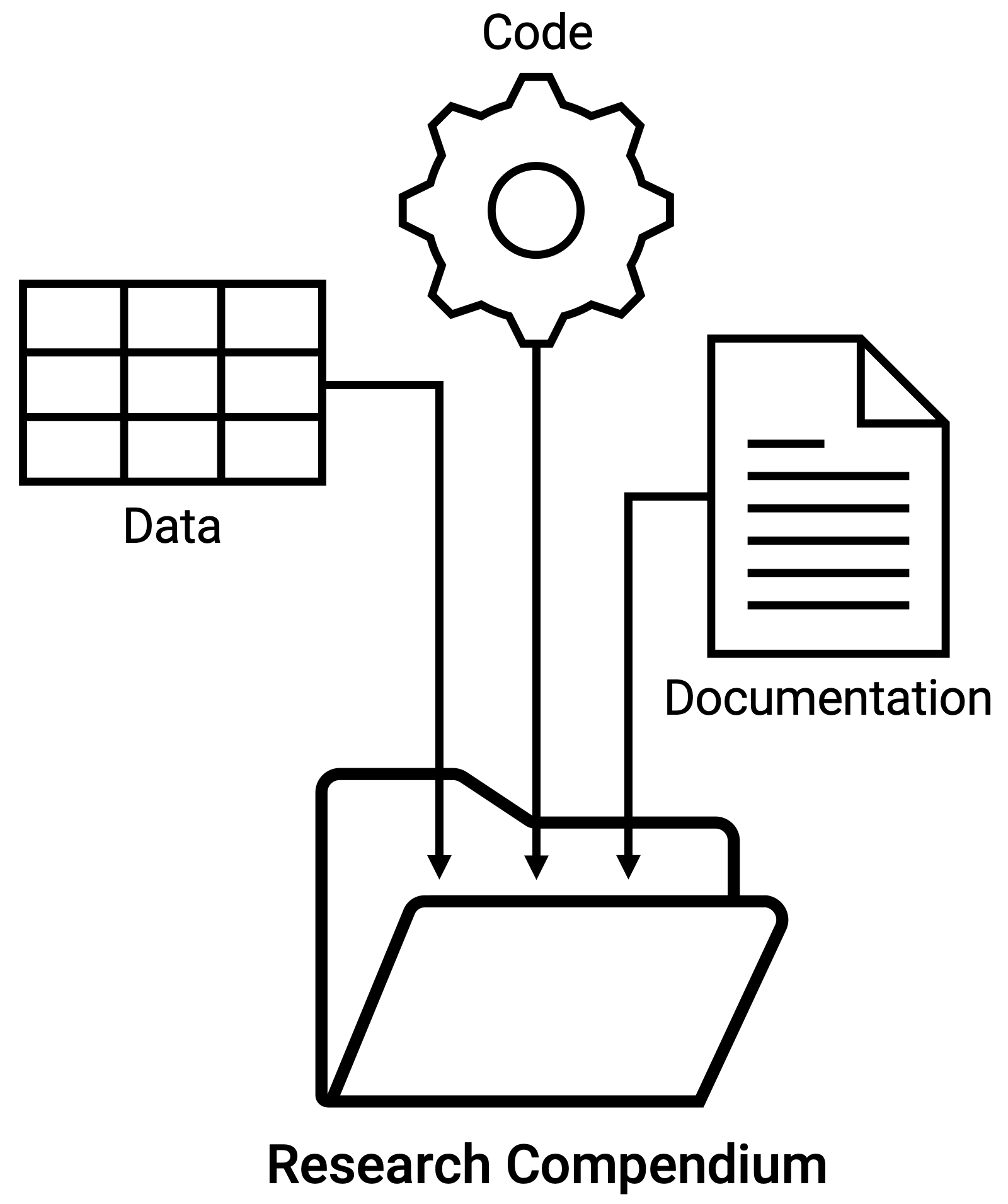

The first known mention of the research compendium concept appeared in an article by Gentleman and Lang (2007), who proposed the compendium as a “new mechanism that combines text, data, and auxiliary software into a distributable and executable unit” (p. 2). Noting the challenges of assembling the artifacts needed to re-run a statistical analysis to computationally reproduce published research results, Gentleman and Lang argued the need to capture the steps of the analytical workflow in a compendium containing one or more “dynamic documents” that encapsulate the description of the analysis (manuscript and documentation), the analysis inputs (data and code), and the computing environment (computational and analytical software).

To put it more simply for this Curating for Reproducibility curriculum, we refer to the research compendium as the collection of the research artifacts necessary to independently understand and repeat the entirety of the analysis workflow from data processing and transformation to producing results.

At a minimum, the research compendium, which may also referred to as reproducibility file bundle or reproducibility package as we define it, contains the following research artifacts:

- Data. Dataset files including the raw or original data, and constructed data used in the analysis.

- Code. Processing scripts used to construct analysis datasets from raw or original data, and analysis scripts that generate reported results.

- Documentation. Information that provides sufficient information to enable re-execution of the analysis workflow including data dictionaries, data availability statements for restricted data, code execution instructions, computing environment specifications, and other necessary details to reproduce results.

The research compendium supports the reproducibility standard by providing access to all of the information, materials and tools necessary to independently reproduce the associated results. Curating for reproducibility applies curation actions to the research compendium.

Spotlight: Curating for Reproducibility: Beyond Data

Curating for reproducibility requires that we think beyond data as the singular object of curation. When considered alone, data that are free of errors, clean of personally identifiable information, and well-documented may be deemed high-quality.

In the context of reproducibility, however, quality standards are applied to the research compendium, of which data is but one component. If an attempt to independently reproduce reported results using the compendium fails, then a quality assessment of the data alone is insufficient.

Curating for reproducibility considers the research compendium as the object of curation, with the goal of ensuring that all of the artifacts contained within it capture all of the materials, information, computational workflows, and technical specifications needed to re-execute the analysis to reproduce published results.

Independently Understandable for Informed Reuse

Curation in support of scientific research has centered commonly on data curation to support long-term access to and reuse of high-quality datasets. It is useful to think about quality not so much as attributes of the data, but as a “set of measures that determine if data are independently understandable for informed reuse” (Peer et al., 2014).

Independent Understandability

Independent understandability is a key curation concept that refers to the ability of anyone unrelated to the production of the data to interpret and use the data without needing input from the original producer(s). That means that in order to enable reuse, data need to be processed, documented, shared, and preserved in a way that ensures that they are “independently understandable to (and usable by) the Designated Community” (a Designated Community is “an identified group of potential Consumers who should be able to understand a particular set of information….[it] is defined by the Archive and this definition may change over time,” (CCSDS, 2012)).

Reusability

The other important concept in data curation is reusability. Motivations for reuse of extant data are varied and include data verification, new analysis, re-analysis, or meta-analysis. Reproduction of original analysis and results, which is the focus of this curriculum, is a type of reuse that sets an even higher bar for quality because it requires that code and detailed documentation–not only the data–to be curated and packaged into a research compendium to allow regeneration of corresponding published results.

Spotlight: 10 Things for Curating Reproducible and FAIR Research

The measures used to determine the quality of a research compendium intended to be used to reproduce reported results are described in the 10 Things for Curating Reproducible and FAIR Research. The 10 Things, summarized below are the output of the Research Data Alliance’s CURE-FAIR Working Group. This international community of information professionals, researchers, funding agencies, publishers, and others interested in promoting reproducibility practices worked together to identify and describe specific requirements for making research reproducible.

CURE-FAIR Working Group. (2022). 10 things for curating reproducible and FAIR research. Research Data Alliance. https://doi.org/10.15497/RDA00074

Knowing what makes research reproducible allows us to recognize research that is not reproducible. The next challenge revisits the scenarios from the challenge in the previous episode to get us thinking about the causes of irreproducibility and their potential consequences.

Exercise: The Impact of Irreproducibility

Consider again the three scenarios from the exercise in Episode 1 (“Reproducibility, Reproducibility, Reproducibility”). Provide responses to the following questions about each scenario.

- What were the causes of non-reproducibility?

- What may have been some consequences of the discovery that the study was not reproducible?

- What could the researchers of the original study have done differently to avoid the issues that rendered the research non-reproducible?

Solution

Scenario 1 (Slicing and Dicing Food Data): All of the research outputs from the food lab have been called into question since the discovery of various problems in studies published by the PI of the lab. The nutrition policies and programs in which the PI played a part may need to be reconsidered in light of accusations of scientific misconduct. The PI’s published research findings were not reproducible because of his failure to provide access to documentation and data that could demonstrate the integrity of his analytic methods and results. Without it, his scientific claims are indefensible. Beyond providing access to documentation, data, and code, pre-registration could have been an effective strategy for preventing the problems seen in the lab’s work and making results analytically reproducible. Pre-registering a study obliges researchers to declare their hypothesis, study design, and analysis plan prior to the start of research activities. Deviations from the plan require documented explanation, which creates greater research transparency.

Scenario 2 (Excel Fail): Governments who implemented austerity measures based on the findings in the original article may not have yielded the expected outcomes and instead exacerbated the economic crisis in their respective countries as a result. The causes of non-reproducibility were primarily due to errors made in the Excel spreadsheet used by the original authors for calculations. Rather than rely on a spreadsheet program, the authors could have used statistical software designed for data analysis to write and execute code to generate results. The code itself reveals the analytic steps taken to arrive at the reported results, which would have enabled the authors (and secondary users) to inspect and verify the validity of their analytic workflow and outputs and promote computational reproducibility.

Scenario 3 (Power(less) Pose): The publication of the power pose research and the scrutiny it was met with happened in the midst of heated arguments among psychologists about the scientific rigor of research produced in their disciplinary domain. Some scholars in the field took umbrage against published studies that presented seemingly unlikely findings and set to work to assess the validity of these findings. What they discovered was widespread abuse of researchers’ degrees of freedom as a means of generating positive, and likely more publishable, results. Because of the publicity it received, this research became something of a poster child of the so-called reproducibility crisis in psychology with its questionable methods and perhaps overstated positive results. This cast widespread doubt not only on those particular research findings, but also on those from the field of psychology writ large. Clear and comprehensive documentation and justification of research protocols used in the power pose experiments would have helped bolster the empirical reproducibility of the research claims.

Challenges to Reproducibility

While much of the research community and its stakeholders have reached the consensus that reproducibility is imperative to the scientific enterprise, it must be acknowledged the challenges that come with efforts to make research reproducible. Indeed for some situations, reproducibility is much easier said than done.

Human Subjects Research

Research that involves human subjects are bound by laws and regulations that place restrictions on data sharing, disallowing their dissemination for any purpose to include verifying the reproducibility of the results of that research. To avoid sanctions from unknowingly failing to protect the identities of study participants, researchers will often decline to share the data or opt to destroy the data upon completion of their analyses.

Copyright and Intellectual Property Rights

As with human subjects research, investigations that use proprietary data and/or code from commercial sources often cannot be redistributed because they are subject to licensing restrictions or intellectual property laws that disallow doing so. Since access to the data and materials underlying research results is a basic requirement for substantiating published claims, proprietary or otherwise restricted data stand as an obstacle to research reproducibility.

Technological Hurdles

Despite having the same data, code, and other research materials used by the original investigator, attempts to computationally reproduce scientific results can prove quite difficult when the technology needed to re-execute the analysis presents challenges. Some analyses require computing environments with exacting specifications that are difficult to recreate. Others are resource-intensive, demanding the processing power of high-performance computing that may not be readily accessible.

Time and Effort

Reproducible research requires the availability of code written using literate programming and includes non-executable comments indicating the function of code blocks; datasets accompanied by codebooks or data dictionaries that define each variable and its categorical value codes; readme files that describe the process for executing the analysis; and any other materials necessary to independently execute the analysis to generate outputs identical to the original results. Preparing these materials may take a great deal of time and effort that researchers just might not have, especially when there is little or no incentive to do so.

Are these challenges insurmountable? Not always. In many cases, strategies exist that account for these challenges to make it possible to still uphold reproducibility standards. In Lesson 4: Compendium Packaging and throughout the Curating for Reproducibility Curriculum, you will learn about these strategies and how to apply them to special cases involving technical complexities, sensitive human subjects data, and restricted proprietary data.

Spotlight: A Reproducibility Dare

When Nicolas Rougier and Konrad Hinsen, the originators of the Ten Years Reproducibility Challenge, issued an invitation to researchers to find the code they used to generate results presented in any article published before 2010 and then use the unedited code to reproduce the results, they suspected that few would succeed.

Ten years is considered an eternity when it comes to the longevity of computations. Rapidly changing technologies render hardware and software obsolete, and evolving computational approaches relegate once novel programming languages to outdated status–in significantly less time than ten years. The 35 entrants confirmed this to be the case, having to resort to using hardware emulators or purchases from online vendors to obtain old hardware, reaching into the depths of memory to revive fading programming language fluency, and confronting poor coding practices that have since been remedied by subsequent years of experience. The difficulty of the challenge cannot be overstated.

One crucial takeaway that participants noted was the importance of documentation to preserve the critical information about where to locate the code, what hardware and software are needed to replicate the original computing environment, and how to run the code to successfully generate expected outputs. While constantly evolving technology can make reproducibility elusive, comprehensive documentation is the key to making it at all possible.

Learn more about the Ten Years Reproducibility Challenge here:

Perkel, J. M. (2020). Challenge to scientists: Does your ten-year-old code still run? Nature, 584(7822), 656–658. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02462-7

Key Points

Reproducible research requires access to a “research compendium” that contains all of the artifacts and documentation necessary to repeat the steps of the analytical workflow to produce expected results.

Curating for reproducibility goes beyond curating data; it applies curation actions to all of the research artifacts within the research compendium to ensure it is independently understandable for informed reuse.

Despite calls for reproducible research, challenges exist that can make it difficult to achieve this standard.