Terms of Use

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

Why is it important to define acceptable uses of the research compendium?

What is the best way to communicate acceptable uses of the research compendium?

How do I determine which type of license to apply to my compendium materials?

Objectives

Understand the importance of articulating acceptable or conditional uses of the research compendium using a license.

Be able to select an appropriate license for a particular research artifact based on its type and specified acceptable uses.

Terms of Use

Ideally, researchers would make their research compendium maximally available by placing the materials into the public domain to allow for unrestricted access and reuse. However, there are various justifiable reasons why this may not be the best option based on applicable laws or professional motives. Datasets that contain sensitive information about human subjects or that are bound by licensing restrictions due to their proprietary nature cannot be shared publicly. A researcher may want to receive formal credit or attribution for creating the materials from others who use them.

Whether a researcher decides to place the research compendium in the public domain or place restrictions and/or conditions on access or use of the research compendium, it is important to articulate for what purpose the materials may be used along with any obligations that come with using the materials.

Licenses

For researchers who have full ownership of their materials and the materials do not present privacy concerns, licenses can be a useful tool for sharing materials without requiring others to request formal permission to use the materials.

A license is a formal document that defines acceptable uses of a work by granting permission and setting conditions. Whereas copyright (as it is defined and enforced by U.S. copyright law) can act as a legal roadblock to reproducibility by conferring exclusive use rights to the creator of research materials, licenses remove this roadblock while still providing the creator a legal framework for enforcing specified acceptable uses and/or conditions for use of the materials.

Spotlight: Licensing “Facts”?

When it comes to applying licenses to research data, questions have been raised about whether or not United States Copyright law allows it. According to 37 CFR Part 202.1, certain materials are not subject to copyright, including “works consisting entirely of information that is common property containing no original authorship, such as, for example: Standard calendars, height and weight charts, tape measures and rulers, schedules of sporting events, and lists or tables taken from public documents or other common sources.” In other words, facts–which often are how data are described–are not copyrightable. For copyright law to apply, a work must be an authored work that is both original and sufficiently creative.

It has been successfully argued that research data can be shown to meet this standard of copyrightable works when originality and creativity is expressed in terms of the author’s selection and arrangement of the data within a database (see Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., Inc., 499 U.S. 340 (1991)). Therefore, while the facts themselves are not subject to copyright, licenses can be applied to structured databases–i.e., datasets–that contain facts.

Read more about the nuances of licensing research data here:

Stodden, V. (2009). Enabling reproducible research: Open licensing for scientific innovation. International Journal of Communications Law and Policy, 13, 22–47. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1362040Carroll, M. W. (2015). Sharing research data and intellectual property law: A primer. PLOS Biology, 13(8), e1002235. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002235

Creative Commons. (2019, October 23). Data. Creative Commons Wiki. https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Data

Selecting a License

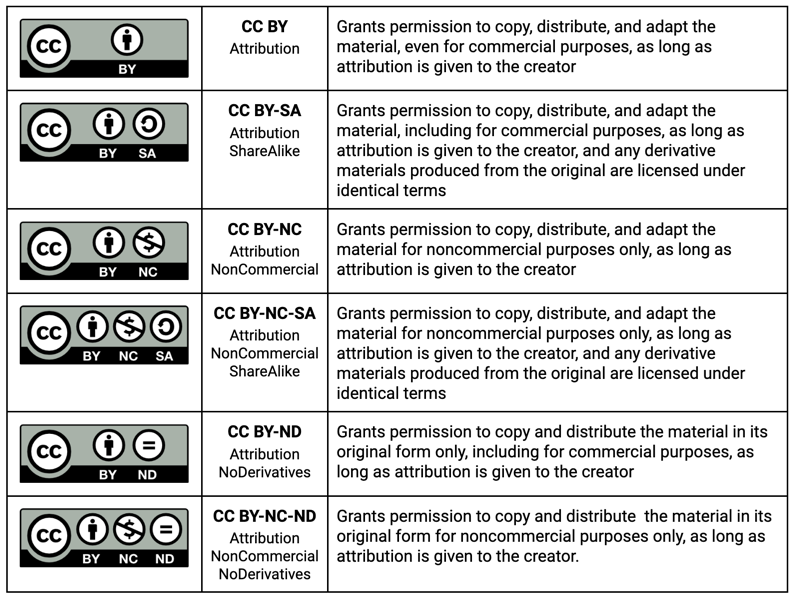

Creative Commons licenses have become widely recognized for its ease of use and understandability. Creative Commons was founded in 2001 as a non-profit organization helping creators make their works publicly available for use under certain conditions and without the encumbrances of copyright.

Creative Commons licenses offer many advantages because they allow creators to select from a range of licenses with different degrees of permissiveness, they offer standardized machine-readable legal text along with easy-to-understand summaries, and they are enforceable worldwide. Below are the license options offered by Creative Commons (version 4.0 International).

For researchers who may want to place their materials into the public domain without any restrictions or conditions of use, Creative Commons offers the CC0 public dedication tool.

By applying CC0 to their materials, the researcher grants permission to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon their materials for any purpose and without conditions.

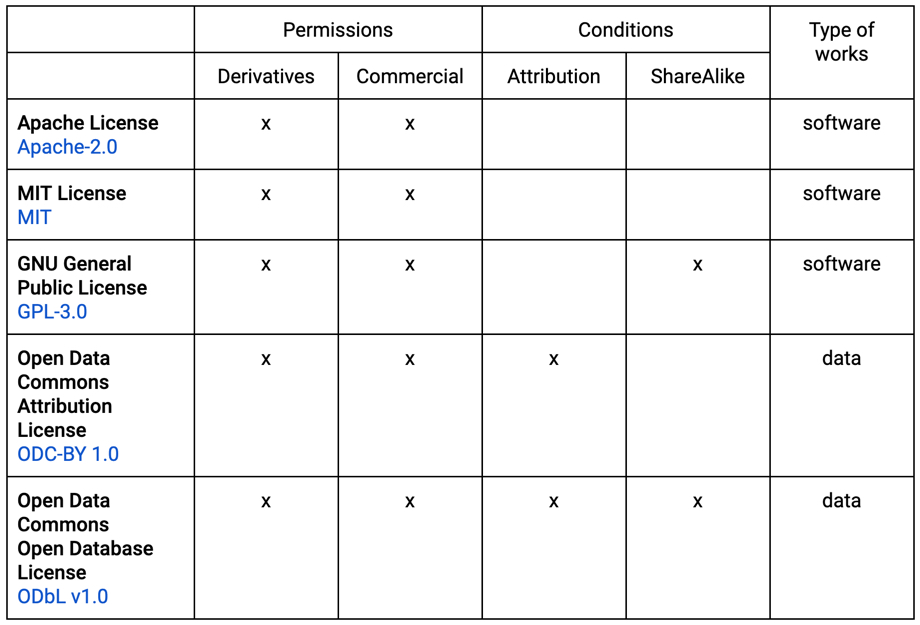

Besides Creative Commons, there are numerous licensing options for researchers to choose from, each allowing declaration of certain use conditions that may not or may not be relevant to a particular type of material. The table below presents a list of other widely used licenses, the permissions and conditions the licenses define, and the types of works to which the licenses are commonly applied.

As with previous episode challenges, putting abstract concepts into action and discussing the reasons behind the choices can strengthen our understanding and confidence in applying those concepts. The next challenge will have you drawing from what you learned about licenses to select an appropriate license for materials included in a research compendium.

Exercise: Pick a License

Compendium description and context.

For each research compendium object listed below, use the Public License Selector tool (http://ufal.github.io/public-license-selector/) or other available resource to select the most appropriate license for the object in the compendium given the type of object and applicable ethical/legal considerations. How would you explain to a researcher why the selected license is appropriate for the given object?

- dataset

- code

- software package

Solution

dataset

solutioncode

solutionsoftware

solution

Discussion: Principles of Scientific Licensing: The Reproducible Research Standard

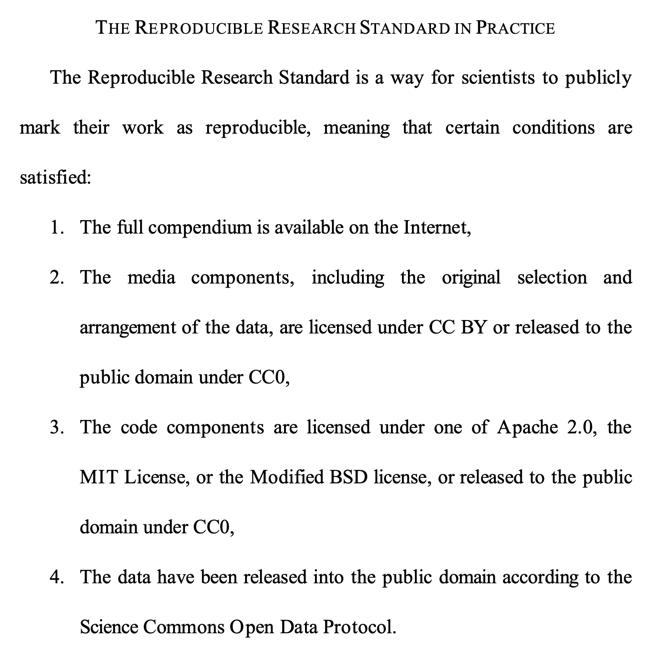

Considering the effect licensing can have on establishing scientific norms for sharing research outputs, Victoria Stodden (2009) proposed the Reproducible Research Standard (RRS) as a structure for ensuring that scientific works are made publicly available under licensing terms that promote openness required for reproducible research:

The RRS proposes that the research compendium be made available to the public under licensing terms that give others permission to copy and use the compendium. Doing so follows the Principle of Scientific Licensing, which states that “Legal encumbrances to the dissemination, sharing, use, and re-use of scientific compendia should be minimized, and require strong and compelling rationale before application” (p. 28).

Thinking about the RRS and the Principle of Scientific Licensing, discuss answers to the following questions:

- Why might a researcher insist that they can/will not implement the RRS for their research compendium?

- What response might you give to that researcher to encourage them to meet the conditions of the RRS?

- What are some “strong and compelling rationales” for applying legal encumbrances to sharing of a compendium?

Stodden, V. (2009). Enabling reproducible research: Open licensing for scientific innovation. International Journal of Communications Law and Policy, 13, 22–47. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1362040

Discussion Points

There are several possible reasons a researcher may insist that they can/will not implement the RRS for their research compendium. Here are some examples:

- The researcher does not hold the copyright to their materials. For example, the data used in their analysis may have been purchased from a commercial data producer.

- The researcher is a champion of Open Science and does not want to encumber their materials with a license. They want anyone who wants to access and reuse the materials can do so without any restrictions.

- The researcher has plans to conduct follow-up studies using their code and data. By allowing anyone to access the materials, the researcher fears that their research will be scooped before they have a chance to publish their findings.

Responses to the above examples may include the following:

- It is possible that the data producer allows redistribution of at least parts of the data used in the analysis. If not, other parts of the compendium, such as the code used to generate the analysis dataset from the original data can be licensed. Be sure to include detailed information on how others can access the data from the original producer.

- Licenses do not have to be restrictive at all. In fact, licenses give others explicit permission to use the materials without restrictions if so desired. By assigning a permissive license to the materials or placing the materials in the public domain under CC0, you are supporting Open Science by signaling to others that the materials are being offered for maximum reuse.

- Providing access to your research compendium affords the community the opportunity to examine the evidence underlying research findings, which is critical to reproducibility. When you provide access, you can also apply an attribution license, which makes it a requirement that anyone who uses your compendium must give you credit as the creator.

Two “strong and compelling rationale” for assigning a restrictive license to data may be that:

- The materials were used under an existing license that required users to apply the same license restrictions as a condition for using the materials (i.e., ShareAlike license).

- The data contain personally identifiable or protected health information that cannot be publicly released, and so licensing is not an option. In this case, the researcher may require users to sign a data use agreement that specifies requirements for mitigating disclosure risks and adhering to laws and regulations governing the protection of human subjects.

Key Points

Placing scientific materials into the public domain to maximize the potential for scientific reproducibility is ideal; however, there may be legal, ethical, and/or professional reasons that unrestricted sharing of the materials is not appropriate.

Licenses remove the impediment of strict copyright laws while still providing a legal framework for enforcing conditions for use of research artifacts.

While there are many different licenses available, it is important to select the license that is most appropriate for the particular artifact based on its type and the conditions under which the artifact can be used.