The Data Quality Review Framework

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is data quality?

What is the relationship between curation and quality?

What is the Data Quality Review (DQR) Framework?

How does the DQR support scientific reproducibility?

Objectives

Explain the relationship between curation and quality

This episode continues the exploration of reproducibility standards taught in Lesson 1: Introduction to Curating for Reproducibility, but with a focus on quality criteria and the curation activities that can ensure that research compendia meet those criteria. Some of these curation activities may be familiar to those with data management and curation experience. However, considering these activities with reproducibility in mind as the primary goal of curation offers a new perspective on the importance of each and every task in the curation workflow, no matter how seemingly trivial. For curation activities that may be unfamiliar, thinking about how they fit into the context of reproducibility helps to appreciate the additional effort taken to obtain the knowledge and skills necessary to perform them.

What is Data Quality?

Great investment is often made to collect data for scientific research. It is essential that the data are of high quality so future users can trust and use the data. But what does it mean for data to be of “high quality”?

Quality data might be conceived as accurate, complete, or timely. Judgments about the quality of data are often tied to specific goals, such as authenticity, openness, transparency, and trust. Different stakeholders may prioritize different aspects of data quality, which may be in conflict with each other. For example, in the rush to produce and disseminate data quickly so that they meet timeliness requirements, the accuracy of the data may be compromised due to the lack of time needed to throughly inspect the data for errors.

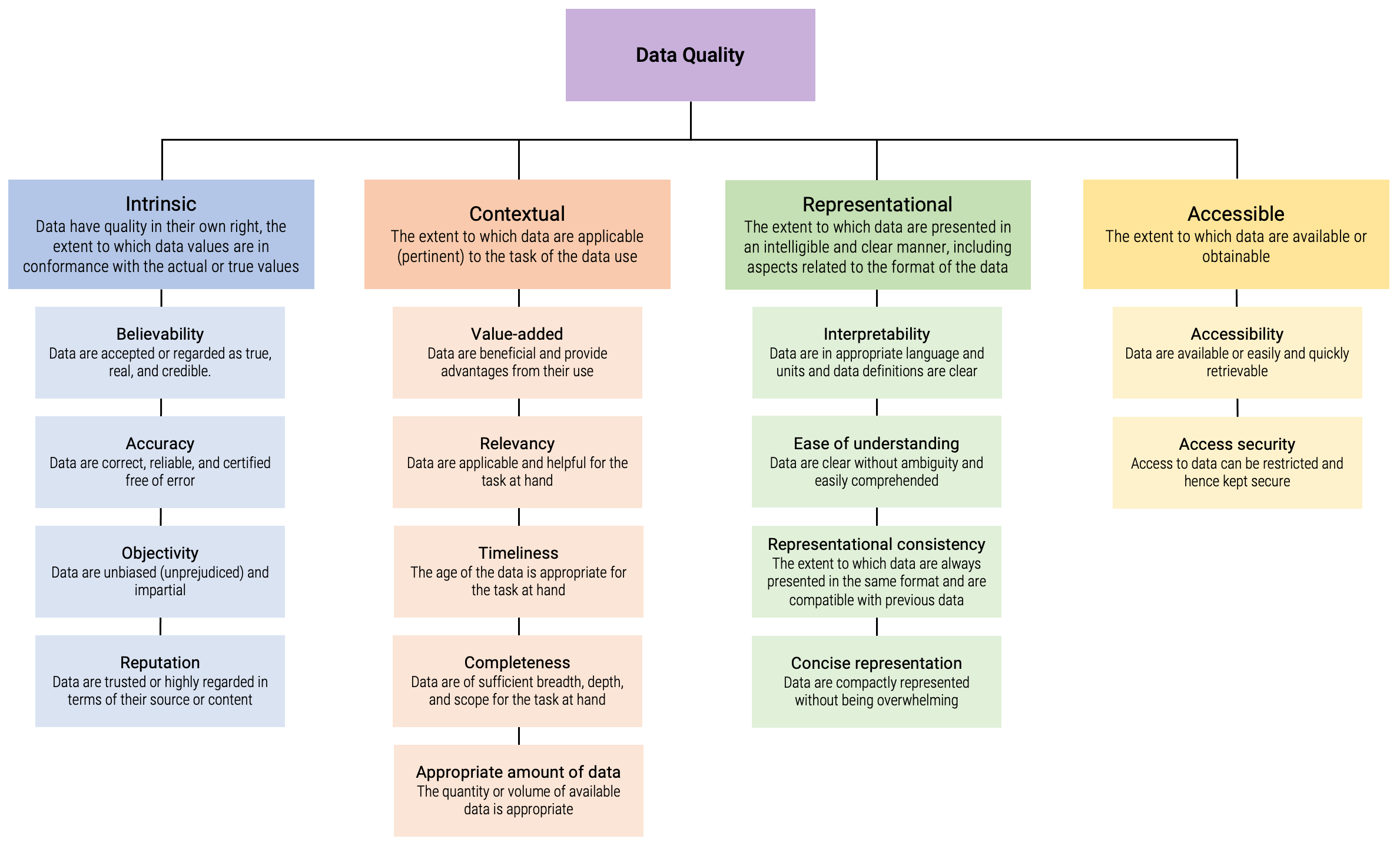

Wang and Strong (1996) defined data quality as having several dimensions, based on surveys of data users who were asked to select from a list of terms those that they perceived to be attributes of data quality. A follow up survey asked data users to then rank those attributes in order of importance to them. Below is the resulting list of 15 data quality attributes grouped into four primary categories.

Assessing quality can seem abstract when thinking about it as a list or hypothetically. The challenges below are tailored to further our understanding of data quality by spending some time with the data quality dimensions. The challenge relies on data quality categorizations defined by Wang and Strong (1996) that include Intrinsic, Contextual, Representational, and Accessible.

Exercise: Assessing Quality: Part 1

This group task is an opportunity for you to think about the different dimensions of data quality and the skills that may be required to assess quality. Instructor note: Consider using a whiteboard or online tool such as Google Jam Board, Etherpad, or similar for this group activity.

- Start by getting into pairs and review the quality dimensions.

- Group each of the data quality dimensions into 4 categories: Intrinsic, Contextual, Representational, and Accessible. In case of conflict, choose the best-fitting category for the dimension. All dimensions must be categorized.

- Your instructor will lead a discussion to establish that we all understand there are different categories of quality, that we are not always talking about the same thing when we talk about data quality, and that some aspects of quality conflict with others.

- If the groups had difficulty grouping the dimensions, discuss why it was so difficult.

Solution

Wang and Strong (1996) categorize data quality into four dimensions:

- INTRINSIC (believability; accuracy; objectivity; reputation) – Denotes that data have quality in their own right, the extent to which data values are in conformance with the actual or true values;

- CONTEXTUAL (relevancy; value-added; timeliness; completeness; appropriate amount) – The extent to which data are applicable (pertinent) to the task of the data user;

- REPRESENTATIONAL (interpretability; ease of understanding; representational consistency; concise representation) – The extent to which data are presented in an intelligible and clear manner, including aspects related to the format of the data (e.g., concise and consistent representation) and meaning of data (interpretability and ease of understanding); and

- ACCESSIBLE (accessibility; access security) – The extent to which data are available or obtainable.

It can be daunting, all the skills needed to do all this work and its many layers. Knowing what we don’t know can be incredibly liberating. Seeking out collaborators if the required skills are not part of your department can help create important relationships and remove the burden from others. Take some time to think about what skills will be needed to do this work and who you can collaborate with on your campus.

Exercise: Assessing Quality: Part 2

This group task is an opportunity for you to think about the different dimensions of data quality and the skills that may be required to assess quality.

- Get into groups of 4-6.

- Discuss the skills that might be necessary in order to assess particular dimensions and categories of data quality from The Assessing Quality: Part 1 challenge. What are the skills? Do you have them? Who in your organization does? Are there any tools you might use to help you? Are there other departments on campus to collaborate with on this?

- The groups report back.

- The instructor will collate reports on a whiteboard and facilitate a discussion about; a) how understanding data quality is a good first step for what we will be learning, b) what it is we will be learning in this lesson, and c) how what we will be learning will help us to solve some of the problems we are facing.

Solution

- Example skills, but not limited to: statistical analysis skills (stats programs for generating descriptive statistics, or more complex analyses if needed to vet submitted data), ability to identify PII/sensitive data both direct and indirect (and knowledge of best practices for redacting or transforming

- Example Departments but limited to: Statistics, various research support departments

The Data Quality Review (DQR) Framework

In the context of curation, it is useful to think about data quality not as much as attributes of the data, but as a “set of measures that determine if data are independently understandable for informed reuse” (Peer et al., 2014).

A data quality review (DQR) is a framework for organizing curation activities in the context of reproducible research. The review activities included in the DQR represent the recommended curation activities that enable a particular reuse of digital materials: The reproduction of reported results using the original materials.

The DQR framework focuses on the digital objects that comprise computation-based scientific claims and, importantly, their interaction. Unlike data curation, which focuses on the dataset as a digital object, DQR is applied to the computation process, and its component parts, that generates the scientific claims.

The DQR combines gold-standard data curation practices and independent reproduction of computation that underlies reported scientific claims.

Spotlight: The DQR and Other Curation Frameworks

The Data Quality Review framework specifically targets computational reproducibility, but it can be used alongside other frameworks, checklists, and tools that support curation, such as the CURATED framework developed by the Data Curation Network (DCN).

The DQR in Practice

The DQR is a process whereby data and associated files are assessed and required actions are taken to ensure files are independently understandable and reusable. This is an active process, involving a review of the files, the documentation, the data, and the code.

The DQR involves a review of the files in the compendium, of the documentation that accompanies the files, and in-depth review of the data and the code (see separate episodes in this lesson for each). These review categories and their associated tasks do not necessarily happen in a linear fashion.

Spotlight: Committing to Data Quality Review

An article published in the International Journal of Digital Curation in 2014 explains what a data quality review entails, who is positioned to carry out such a review, and what it means to commit to such a review. The article examines the review practices of three domain-specific data archives and three general data repositories, finding that general data repositories fall short of full data quality review and that long-standing data archives, particularly in the social sciences, implement many review activities, but typically not code review.

The article argues that commitment to data quality review is a community effort, involving researchers, academic libraries, scholarly journals, and others: “the stakeholders and caretakers of scientific materials, such as data and code, must share the responsibility of meeting the challenges of data quality review in order to ensure that data, documentation, and code are of the highest quality so as to be independently understandable for informed reuse, in the long term. The commitment to data quality review, however, has to involve the entire research community.”

Peer, L., Green, A., & Stephenson, E. (2014). Committing to data quality review. International Journal of Digital Curation, 9(1). http://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v9i1.317

Discussion: Food for Thought About Review

Roger Peng, an advocate of reproducible research, argues that articles that have passed the reproducibility review ‘convey the idea that a knowledgeable individual has reviewed the code and data and was capable of producing the results claimed by the author. In cases in which questionable results are obtained, reproducibility is critical to tracking down the “bugs” of computational science.’

Peng, R.D. (2011). Reproducible research in computational science. Science, 334 (6060), 1226-1227. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1213847

Questions for discussion:

- Is this something that researchers want?

- What happens when you find a mistake?

- Who is in the best position to do such a review?

- How does the labor of review figure into the research process as a whole, and authorship in particular?

- How do disciplinary norms play into this?

The Object of Review: The Research Compendium

When we talk about computational reproducibility, we necessarily include more than one file. At minimum, we need a computer script and input data. Let’s recall what our goal is here: to find out whether data and code are available and sufficient to produce the same results, and whether the programs run. But we also want to ensure that files are independently understandable for informed reuse.

The four basic components of a reproducibility package are:

- Data

- Code

- Documentation (e.g., README, codebook)

Other materials that may be included:

- Code output matrix

- Comparison output

- Treatment materials

Spotlight: The Whole is Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts

Do we care about the package as a whole or about its constituent parts? That depends on what you want to do with it. Some users may want to use or examine only one component of the reproducibility package, the data, for example. Others prefer a frictionless process whereby they can test the package as a whole, for example, via ‘Push-Button Replication’ (see this project from 3ie: https://www.3ieimpact.org/our-expertise/replication/push-button-replication).

The Process of Review

The review process is often iterative, not linear. That is, data review may require that a script be run to apply labels. Inspecting the code can shed light on additional necessary files that you missed in the file review. Code can produce a codebook, modifying your documentation review. And, during code review, comparing the output to the manuscript may require modifications to earlier conclusions during the code inspection.

As a curator, you need to be able to work iteratively and to track your process. You may also likely need to interact with authors to resolve any lingering or unresolved issues.

Spotlight: Curation is Not a Linear Process

It is important to note that curation work in general, and curation frameworks in particular, do not necessarily prescribe a strict workflow or sequence. Procedures may vary depending on the materials (e.g., the data), on curator skills, on policy, on data creator feedback, and more. The key is that all curation activities should be performed before a review is complete.

Keeping Track of the Review and Communication with the Researcher

There will be some communication with authors about missing information. Organizations that take on DQR should think through some key issues such as:

- What are the mechanisms for keeping track of where you are in the review? Any problems you find before accepting the submission?

- How to set standards for what to send back to researchers and what to accept?

- How are we handling communication with researchers? How to handle delayed responses from researchers?

Spotlight: Curation Process Management

The curation workflow has many steps and can involve several stakeholders. Managing the curation workflow and keeping track of curation activities can quickly become challenging. A few recent approaches attempt to address the challenges of managing and tracking the curation process, which will also help standardize the process. Here are some examples:

Checklist: The CURATE(D) steps are a teaching and representation tool. This model is useful for onboarding data curators and orienting researchers preparing to share their data. a standardized set of C-U-R-A-T-E-D steps and checklists to ensure that all datasets submitted to the Network receive consistent treatment (DCN, 2018).

Data Curation Network (2022). CURATE(D) Steps and Checklist for Data Curation, version 2. http://z.umn.edu/curate.

Software: The Yale Application for Research Data (YARD) is an adaptable curation workflow tool that enhances research outputs and associated digital artifacts designated for archival and reuse. By tracking curation tasks, YARD supports a transparent and documented workflow that can help researchers, curators, and publishers share responsibility for curation activities through a single pipeline.

Peer, L., & Dull, J. (2020). YARD: A Tool for Curating Research Outputs. Data Science Journal, 19(1), 28. http://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-028

The remaining Episodes in this Lesson will outline the recommended curation activities for performing file, documentation, data, and code review.

Key Points

It is essential that the data are of high quality so future users can trust and use the data.

There are many different dimensions of data quality, and different stakeholders may prioritize different ones.

Reproducibility–the ability to reproduce original analysis and results–sets an even higher bar for quality.

The Data Quality Review (DQR) framework is a set of recommended curation activities that promote the reproducibility of the research.

DQR involves a review of the files, the documentation, the data, and the code being curated.