Code Review

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

Why is code review important for reproducibility?

What curation activities are associated with code review?

Objectives

Basic understanding of what is involved in code review

Providing examples of common code issues when attempting computational reproducibility

In this episode, we unpack the Data Quality Review Framework, focusing on Code Review. Please note that Episodes 2-4 (File, Documentation, and Data Review) in this lesson may include material familiar to many data curators. In this Episode 5 on Code Review, we introduce the additional curation activities that specifically involve code. The work done in Lesson 2 can be considered the pre-work necessary to continue the work in this Episode.

Lesson 3: Reproducibility Assessment is entirely dedicated to the practice of code review in support of reproducible research.

What is Code?

In the context of this lesson, code refers to the computer code necessary to perform data-related operations such as cleaning, transforming, or analyzing. Related, a script refers to a collection of code, usually pertaining to a particular step in the data analysis, for example.

Code files commonly used in research include the following extensions: .do, .R, .Rmd, jupyter, jl, py.

“Code in data-intensive research is generally written as a means to an end, the end being a scientific result from which researchers can draw conclusions [e.g., gain statistical insight into distributions or create models using mathematical equations]. This stands in stark contrast to the purpose of code developed by data engineers or computer scientists, which is generally written to optimize a mechanistic function for maximum efficiency.” Stoudt, S., Vásquez, V. N., & Martinez, C. C. (2021). Principles for data analysis workflows. PLoS Computational Biology, 17(3), e1008770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008770

See the examples of scripts below.

Data generating, cleaning, or transformation:

//Labeling variables

label variable treatment "The manipulation group"

label define treatment1 1 "$4" 2 "$"

label variable treatment treatment1

label variable pieces "How many pieces of pizza did you eat today?"

label define ideolab -3 "V. Lib." -2 "Lib." -1 "S. Lib." 0 "Middle" 1 "S. Cons." 2 "Cons." 3 "V. Cons." 4 "" 5 "DK/Can't place"

//recoding variables

recode region (1/2=1 "Northeast") (3/4=2 "Midwest") (5/7=3 "South") (8/9=4 "West"), gen(region_4cat)

//generating variables

generate gp100m = 100/mpg

label var gp100m "Gallons per 100 miles"

Data analysis:

tab price foreign, chi2

reg price mpg foreign weight

Create tables and figures:

#########

#########TABLE 2: Cross tabulation of unfairness views and racial resentment

#########

plotdata <- cbind(100*prop.table(table(survey$unfair_my[survey$race_1==1],survey$res_fav2[survey$race_1==1])),

100*prop.table(table(survey$unfair_my[survey$race_1==1],survey$res_dis2[survey$race_1==1])))

rownames(plotdata) <- c("Not Unfair to Own Race","Unfair to Own Race")

colnames(plotdata) <- c("Not Resentful","Resentful","Not Resentful","Resentful")

print(xtable(plotdata, digits=0,label="tableres", caption="Among white respondents, the incidence of unfairness perceptions and two common measures of racial resentment. See footnote \\ref{questionwording} for question wording."),

floating = TRUE, file="table2.tex")

Saving or logging:

log using stata_exercise.log, replace

Why Review Code?

The term code review comes from software development, where it is common and integral practice (see Google documentation on how to conduct a code review). Code review refers to a systematic approach to reviewing other programmers’ code for mistakes and other quality metrics. The review of one’s code is conducted by a team member who typically assesses whether requirements are included, how readable the code is, whether it conforms to a specific style, etc. In this context, the goal of code review is to improve the overall code health over time. Other benefits of code review are sharing knowledge so that no single developer is the “critical path” and helping facilitate conversations about the code base.

In the context of curating for reproducibility, the primary reason to review code is that non-reproducibility is a threat to the scholarly record. It is not uncommon in labs that analysis scripts or software are written by a postdoc or graduate student. Often, the code is elaborated over time and can become quite cumbersome (e.g., over 30K lines of code in multiple files) and complicated such that only the original postdoc can make changes and add features. It is inevitable that research teams grow and change and original authors cannot be reliable sources of information or explanations when something goes wrong.

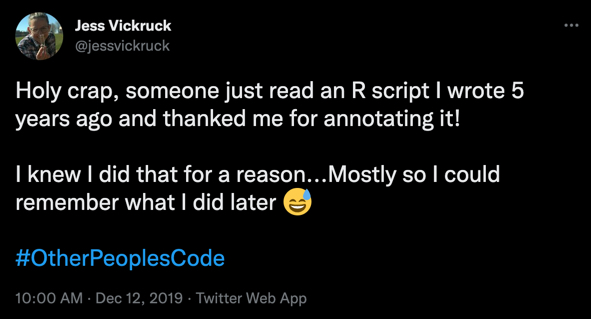

Another reason is methods transparency: Transparent sharing of data and results is the first fundamental step to open research. How the data are analyzed to reach results should be just as transparent. Code not only performs operations on the data, it also serves as a log of analytical activities, allowing future users to understand any unintentional errors or mistakes.

In addition, considering that, in general, code is read more often than it’s written, we may want to review code because it reflects a particular or new way of thinking about a problem. Code communicates research decisions, methodologies, and results. It reveals a mindset or approach, and is more than just something that happened to work. Reviewing the code in detail not only helps ensure that it will be functional, but also that it can be applied to other data or to a common pattern encountered elsewhere.

Code Review in Practice

“Similar to data files, code files should also be subject to examination and potential enhancement to provide transparency and enable future informed reuse. A data quality review requires that code is executed and checked, that an assessment is made about the purpose of the code (e.g., recoding variables, manipulating or testing data, testing hypotheses, analysis), and about whether that goal is accomplished.” (Peer et al., 2014)

Discussion: Who Should Conduct a Code Review?

Before turning to the practice of code review, it might be a good time to pause and ask,

- Who is responsible for verifying reproducibility? And, more generally, who is responsible for the quality of research data and code deposited in repositories? Consider the Pros and cons of the following options:

- Original author(s)

- Informal peer network (e.g., collaborator, friend in the department)

- Formal peer network (e.g., peer reviewers, third party verifiers)

- Archive and repository staff

- Other?

- Will peer code review discourage scientists from sharing code?

Lesson 3: Reproducibility Assessment of the Curating for Reproducibilty Curriculum is entirely dedicated to the practice of code review in support of reproducible research.

Key Points

Difficulties with executing code can prevent computational reproducibility.

Researchers should write code with reproducibility in mind.

Curators reviewing the code can take steps to ensure that it is executable and documented to facilitate reproducibility.